Understanding the commercial real estate loan underwriting process can give you an advantage when seeking debt financing for a commercial property. In this article, we’ll discuss how lenders underwrite commercial real estate loans, and how to determine the maximum loan amount for a property. We will also cover how underwriting changes for different loan types, including bridge, construction, and homebuilder loans.

Loan Types at a Glance

Not all commercial real estate loans are underwritten the same way. The framework is similar, but the details vary depending on the type of property and stage of the project:

- Stabilized acquisition or refinance: Based primarily on in-place Net Operating Income (NOI) and property value.

- Bridge loan: Underwritten on both current NOI and a proforma NOI that reflects the borrower’s business plan.

- Construction loan: Driven by loan-to-cost (LTC) and as-complete value, with interest reserves built in. NOI becomes important later at stabilization.

- Homebuilder or development line of credit: Based on absorption pace, advance limits, and aging limits, not on NOI.

In this article we will focus on stabilized loans as the base case, then point out how the approach differs for other loan types.

Preliminary Discussions

Before a new loan goes through the full underwriting and credit approval process, the lender and the borrower will often have a preliminary discussion. The purpose of this discussion is to give the lender a better understanding of the project and to also learn how the bank might structure the loan.

At this stage you will often discuss:

- Current interest rates

- The bank’s loan policy

- Target ratios such as LTV, DSCR, and debt yield

- Amortization schedules, terms, and prepayment flexibility

Borrowers may also submit a rent roll, a proforma, and other supporting documents. The loan officer will usually take all this information and discuss it internally with a senior lender or credit officer. If the lender is comfortable with the project and supporting documents, they will prepare a term sheet, which is a basic outline of their proposed loan terms and conditions. If the term sheet is agreeable to both parties, then the loan will move into the full underwriting process.

For example, a stabilized office building will be subject to requirements such as LTV, DSCR, debt yield, amortization, and term limits. A construction loan may instead be evaluated using loan to cost ratios, interest reserves, and preleasing tests. A homebuilder line of credit will add considerations such as advance limits and aging limits.

Let’s take a look at what the bank’s underwriting process might look like for an existing, stabilized property. Although we’ll outline the process in clear steps in this article, keep in mind that in practice many of these steps overlap or happen simultaneously. For example, a lender may begin reviewing borrower financials while also normalizing NOI, or update stress tests once new appraisal data arrives. Underwriting is best thought of as an iterative process rather than a perfectly linear checklist.

Step 1: Normalizing Net Operating Income (NOI)

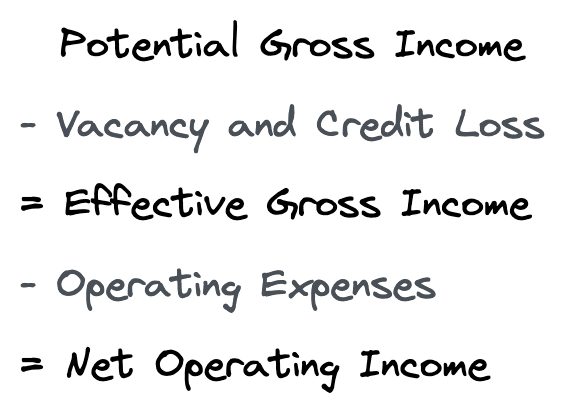

The first step in commercial real estate loan underwriting for an already existing property is determining the appropriate Net Operating Income (NOI). The borrower will typically submit a rent roll and a proforma, but the lender will almost always construct their own proforma for loan underwriting purposes, which may result in a different NOI calculation. Possible lender adjustments to NOI include increasing the vacancy and credit loss factor to account for changing market conditions, tenant rollover risk, or deducting reserves for replacement.

This process ensures NOI reflects sustainable performance. For stabilized loans, normalized NOI becomes the foundation for sizing. For construction, it becomes relevant at the point of stabilization and take-out.

After determining NOI, lenders have internal loan policy guidelines they use as underwriting criteria for different real estate projects. The most important loan underwriting criteria used are the Loan to Value Ratio (LTV) the Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR), and the Debt Yield.

Step 2: Apply Core Underwriting Ratios

After estimating a normalized NOI, lenders typically calculate three key metrics to determine the maximum loan amount.

- Loan-to-Value (LTV): Loan ÷ Value. Value is usually estimated by dividing NOI by a market cap rate. A third-party appraisal later supports or adjusts this figure.

- Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR): NOI ÷ Annual debt service. Debt service depends on interest rate, amortization, and whether there is an interest-only period.

- Debt Yield: NOI ÷ Loan amount. Provides a leverage-neutral test that does not depend on interest rate or amortization.

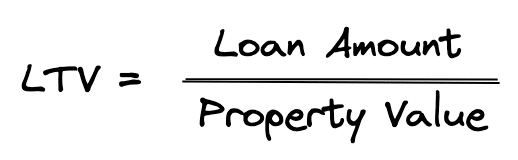

Loan to Value Ratio (LTV)

The loan to value ratio is simply the ratio of the total loan amount borrowed in relation to the value of the property.

For example, suppose the requested loan amount for a commercial real estate property was $1,000,000 and the appraisal came in with a value of $1,250,000. The LTV ratio would simply be $1,000,000/$1,250,000, or 80%.

Different banks usually have different but similar LTV requirements. This is driven by each bank’s internal strategic growth goals and existing portfolio concentrations. LTV guidelines also vary by property type to reflect variations in risk. For example, land is considered to be riskier than a stabilized apartment building, and as such the required LTV on land will be lower than on an apartment.

A critical issue with the loan to value ratio is how a lender determines value. During the initial underwriting, a lender will typically use the borrower’s requested loan amount and its own internal estimation of value. Before a loan commitment is issued, a third-party appraisal firm is also normally engaged during the full underwriting process to provide an appraisal report on the property. However, it’s worth noting that the lender doesn’t have to fully accept the appraised value and can still make downward adjustments to the appraised value.

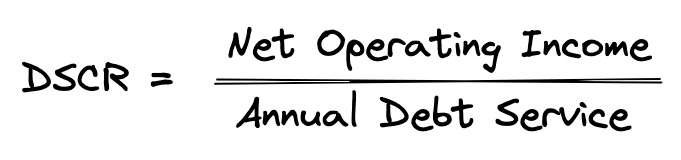

Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR)

The debt service coverage ratio is the ratio of NOI to annual debt service. The reason this ratio is important to lenders is that it ensures the property has the necessary cash flow to cover the loan payments. The DSCR formula can be calculated as follows:

The DSCR gives the lender a margin of safety. For example, by requiring a 1.20x DSCR the lender is building in a cushion in the property’s cash flow over and above the annual debt service. At a 1.20x DSCR the property’s NOI could decline by 17% and the loan payments would still be covered.

Like the LTV ratio, the DSCR is set internally by the bank’s loan policy and can vary by property type. For instance, riskier properties like self-storage will typically have higher DSCR requirements than more stable properties like apartments.

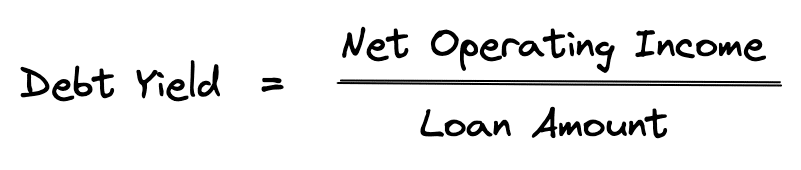

Debt Yield

Debt yield is the ratio of NOI to the loan amount. Unlike DSCR, which depends on interest rate and amortization, debt yield is a simple, leverage-neutral test. The formula can be calculated as follows:

The reason this ratio is important to lenders is that it shows how much income a property produces relative to the size of the loan. For example, a 10 percent debt yield means the property generates $10 of NOI for every $100 of loan balance.

Debt yield gives the lender a cushion that is independent of changing interest rates or repayment terms. Many lenders require a minimum debt yield, often in the range of 8 to 10 percent. Riskier property types or transitional projects may have higher minimums, while more stable assets like multifamily can sometimes qualify with lower thresholds.

After the financial crisis of 2008, when interest rates were artificially low and cap rates were compressed, DSCR could be met even on highly leveraged loans. Debt yield emerged as a go-to metric for lenders, particularly in the CMBS market, because it provided a simple, standardized gut check on risk that was not distorted by the rate environment.

Introducing CRE Loan Underwriting

The only online course that shows you how lenders underwrite and structure commercial real estate loans

Reviews key loan personnel at each stage of the loan approval process

Learn fundamental credit concepts used by all lenders

Understand the framework lenders use to underwrite any type of loan

5 detailed case studies using actual real world loans

Package of more than a dozen tools and templates you can download and use

60-day money back guarantee

Step 3: Maximum Loan Analysis

The lender now solves for the maximum loan supported by each ratio and takes the lowest number. This becomes the maximum supportable loan.

The purpose of the maximum loan analysis is to determine the maximum supportable loan amount based on the NOI, the DSCR, and the LTV requirements. Once a lender calculates the net operating income, they will then calculate the loan amount using the loan to value, debt service coverage, and sometimes debt yield guidelines. Next, the lender will then take the lesser of the loan amounts calculated based on each approach, and this will be the maximum supportable loan amount.

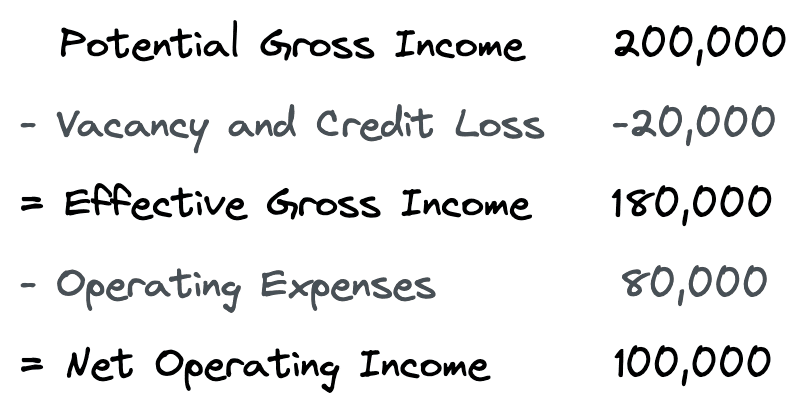

Let’s look at an example to clarify how this works. Suppose that you are acquiring a multi-tenant office property with the following stabilized NOI:

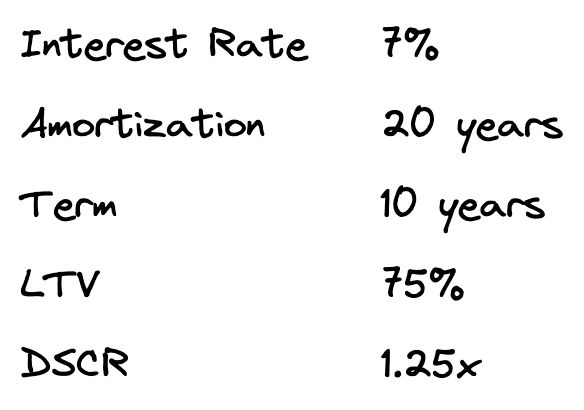

Further, suppose that after talking to your lender, you learn their current underwriting guidelines on this type of property are as follows:

Current interest rates are at 7%, and they would require a 1.25x DSCR using a 20-year amortization, with a maximum LTV ratio of 75%. Using all this information, let’s complete a maximum loan analysis to see how big of a loan you can get for your property.

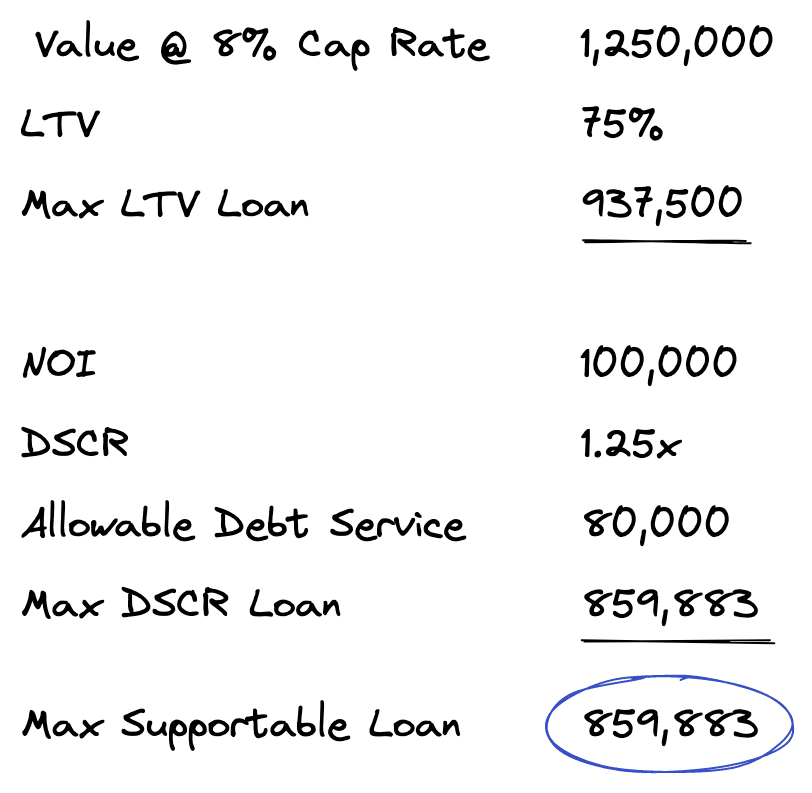

The analysis above shows how a bank would initially look at this loan request using the LTV and DSCR only.

First up is the maximum loan amount using the LTV approach. To find the maximum loan using this approach, the lender will estimate a value of the property at an appropriate cap rate. Initially, the cap rate used will be based on the lender’s knowledge of local market conditions, but ultimately the value must be supported by a third-party appraisal. In our example, the NOI of 100,000 is divided by 8% to get an approximate value of 1,250,000.

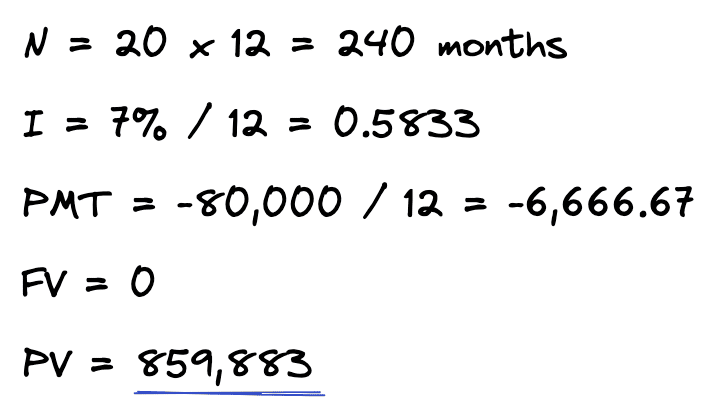

Next is the maximum loan amount based on the DSCR approach. To find the maximum loan using this approach, the lender will first take the NOI and divide it by the required DSCR. This will result in the portion of NOI that can be used to pay debt service each year. In our example, this is 100,000 / 1.25, or 80,000. In other words, if our NOI is 100,000 and our annual debt service is 80,000, then we would have 100,000 / 80,000 or 1.25x, which is the debt service coverage ratio needed to satisfy the bank’s requirements.

The lender can now use this allowable debt service of 80,000 to back into a loan amount. To accomplish this, we just need the interest rate and the amortization period to solve for the present value of the loan. Using a financial calculator, we can plug in these known variables and then solve for the present value, which is the loan amount.

Now the lender has two maximum loan amounts, one based on the LTV approach of 937,500, and another based on the DSCR approach of 859,883.

The last step in calculating the maximum supportable loan amount for the property is to take the lesser of these two amounts. In our case, this results in a maximum loan amount of 859,883, which would likely be rounded down to 859,000. Although in practice, lenders might also use the debt yield as a third approach.

Maximum Loan Analysis Cheat Sheet

Fill out the quick form below and we’ll email you our free maximum loan analysis Excel cheat sheet containing helpful calculations from this article.

Step 4: Stress Testing the Loan

Before finalizing terms, lenders want to know how resilient a deal will be under adverse conditions. Stress testing is the process of adjusting key assumptions to see how the loan performs if the market does not cooperate. This step often reveals hidden risks and can directly influence the loan structure.

Common stress tests include:

- Interest rate shocks. Lenders may increase the interest rate by 100 to 200 basis points to see if DSCR still clears their minimum threshold. This is especially important for floating-rate loans.

- NOI declines. Underwriting models are often run with a 5 to 10 percent drop in NOI to simulate tenant rollover, unexpected vacancy, or declining rental rates. If coverage falls below policy minimums under these scenarios, the loan may be downsized or structured more conservatively.

- Breakeven occupancy. Lenders calculate the occupancy rate at which NOI falls just low enough to cover debt service. For example, if a property requires 70 percent occupancy to meet debt service, that leaves a smaller cushion than one that breaks even at 55 percent. Breakeven occupancy highlights how much vacancy a property can absorb before it fails to cover the loan.

- Cap rate expansion. For loans sized partly on value, lenders may increase the cap rate by 50 to 100 basis points to test whether the collateral cushion still holds. If the adjusted value produces an unacceptably high LTV, the loan amount may be cut back.

For value-add and construction loans, stress tests can be even more detailed. Lenders may push out lease-up timelines, increase construction costs, or reduce projected rents. These tests show how sensitive the project is to delays or overruns.

Stress testing gives credit officers confidence that the property can weather setbacks, and it helps determine what loan structure will be required. If stress results show thin margins, the lender may respond by tightening covenants, requiring additional reserves, or asking for more recourse.

Step 5: Borrower and Guarantor Analysis

Alongside the property itself, lenders also analyze the financial strength of the borrower and guarantors. This review helps the bank confirm that the people behind the deal have the capacity to support the loan if the property does not perform as expected.

Key areas of focus include:

- Net worth and liquidity. Many banks require guarantors to have a net worth at least equal to the loan amount and liquidity sufficient to cover several months of debt service and operating expenses.

- Global cash flow. Lenders may evaluate the borrower’s entire portfolio of real estate and businesses to make sure overall obligations are covered.

- Credit history. Payment history, outstanding debt, and overall credit profile are considered.

- Contingent liabilities. Guarantees on other loans, pending lawsuits, or other obligations can reduce a borrower’s ability to support the property if performance weakens.

The results of this analysis often influence loan structure. For example, weak guarantor liquidity may lead to larger reserves, or a lack of experience may trigger recourse requirements. Strong financials and experience, on the other hand, can help borrowers negotiate more favorable terms.

Step 6: Qualitative Review

Alongside the financial analysis, lenders weigh qualitative factors that can make or break a deal. These include:

- Sponsor experience. Has the borrower successfully managed or developed similar properties in the past? Track record carries significant weight.

- Property quality. Location, age, physical condition, and tenant mix all matter. Lenders prefer properties with strong locations, durable construction, and staggered lease rollover schedules.

- Market conditions. Supply and demand, pipeline of new construction, comparable rents, and local employment trends can tip the scales. Even a strong sponsor and property may struggle in a weak market.

- Operational capacity. Banks look at whether the sponsor has competent management and reporting systems in place. Reliable property managers, realistic budgets, and clear oversight give lenders more confidence.

- Feasibility of the business plan. For transitional or construction projects, lenders test whether lease-up, renovation, or exit assumptions are realistic.

This qualitative layer ensures the loan is not just financially sound on paper, but also supported by the sponsor’s capabilities and market fundamentals.

Step 7: Loan Structure

With an understanding of the financials and qualitative factors, lenders finalize how to structure the deal. The goal of loan structure is to balance risk protection for the bank with flexibility for the borrower.

The key elements of loan structure include:

- Recourse. Most CRE loans are non-recourse, meaning the borrower is not personally liable beyond the collateral. Riskier loans may require partial or full recourse tied to guarantor net worth and liquidity.

- Repayment profile. This covers amortization, interest-only periods, and maturity with possible extensions. Extension options usually require the property to meet minimum DSCR or debt yield tests.

- Prepayment and rate protection. Lenders often use prepayment penalties such as yield maintenance, defeasance, or step-down schedules. Floating-rate loans may also require interest rate caps or swaps to limit rate risk.

- Reserves and escrows. These set aside funds for taxes, insurance, replacement reserves, and sometimes tenant improvements or leasing commissions. Construction loans typically include interest reserves as well.

- Cash management and covenants. If a property looks vulnerable, lenders may require a lockbox or cash sweep triggered when DSCR or debt yield falls below policy levels. Other covenants can include limits on leverage, financial reporting requirements, or restrictions on transfers.

For construction or heavy value-add projects, structure may also include budget approvals, completion guarantees, and draw controls. These protections ensure the lender has a clear path to repayment even if the project encounters delays or cost overruns.

Step 8: Credit Approval

Once underwriting is complete, the loan request is summarized in a credit memo. The credit memo brings together the financial analysis, stress testing, qualitative factors, and key risks with proposed mitigants.

The approval process varies by institution and by loan size. Smaller loans may be approved by a single senior credit officer, while larger or more complex loans typically go before a formal credit committee made up of senior executives and, in some cases, outside board members.

Regardless of format, the review covers both the quantitative side of the deal (NOI, LTV, DSCR, debt yield, stress tests, and borrower/guarantor analysis) and the qualitative side (sponsor, property, and market). Approvals are often conditional, requiring updated financial reporting, completion of third-party reports, or funding of additional reserves before closing.

Step 9: Closing and Monitoring

When a loan closes, the legal documents are signed, reserves are funded, and funds are disbursed. But underwriting does not end at closing. Banks continue to monitor loans throughout their life, which usually includes:

- Annual financial statements and rent rolls from the borrower

- Ongoing DSCR or debt yield testing

- Property inspections and occasional updated valuations

In addition to these monitoring requirements, borrowers must comply with the covenants written into the loan agreement. These can include minimum DSCR or debt yield levels, restrictions on additional debt, limits on equity transfers, or ongoing guarantor net worth and liquidity requirements. If covenants are breached, lenders may require a cash cure, additional reserves, or other corrective action.

If performance declines or covenants are not met, the lender can downgrade the loan, restrict cash distributions, or trigger remedies designed to protect their position. Covenant compliance is therefore a critical part of loan management and not just a formality.

How Underwriting Differs by Loan Type

While the framework above describes stabilized loans, other loan types require different approaches.

- Bridge loans. Lenders evaluate both current NOI and a proforma NOI. The business plan, lease-up timeline, and exit strategy receive heavy scrutiny. Stress tests often focus on whether the borrower can achieve projected NOI fast enough to refinance or sell. Exit DSCR and debt yield are key because they show whether the property will support a take-out loan at stabilization.

- Construction loans. These loans are sized based on loan-to-cost and as-complete value. Lenders build in interest reserves to cover debt service during construction and lease-up. They also require strong budget controls, completion guarantees, and contingency funds. While current NOI is not relevant, proforma NOI becomes critical when the project stabilizes and the construction loan is refinanced into permanent financing.

- Homebuilder and development loans. These facilities are not underwritten on NOI at all. Instead, lenders focus on the pace of lot or home sales, inventory controls, and guarantor strength. Advance rates determine how much can be borrowed against land, finished lots, and model homes. Aging limits require paydowns if inventory remains unsold too long. Because repayment depends on sales absorption rather than rental cash flow, sponsor liquidity and market demand are especially important.

Conclusion

Commercial real estate loan underwriting is a structured process that combines both quantitative analysis and qualitative judgment. Lenders begin by normalizing NOI, applying core ratios like LTV, DSCR, and debt yield, and running a maximum loan analysis. They then stress test the deal, evaluate the financial strength of the borrower and guarantors, and review property quality and market conditions. From there, the bank shapes the loan structure, presents the deal for approval, and monitors performance long after closing.

Although stabilized loans follow the most straightforward path, bridge, construction, and development loans introduce additional layers of complexity. Each type requires lenders to adapt the framework to the realities of the project and the risks involved.

For borrowers, understanding how lenders approach underwriting is an advantage. It allows you to prepare better documentation, anticipate lender concerns, and structure your project in a way that aligns with policy requirements. Ultimately, the goal of underwriting is not just to protect the lender, but to ensure that the loan is sound, sustainable, and positioned for long-term success.

Do you need help building a proforma and quickly running a maximum loan analysis, complete with presentation-quality PDF reports? You might consider trying our commercial real estate analysis software with a free trial.