The debt yield is becoming an increasingly important ratio in commercial real estate lending. Traditionally, lenders have used the loan to value ratio and the debt service coverage ratio to underwrite a commercial real estate loan. Now, the debt yield is used by some lenders as an additional underwriting ratio. However, since it’s not widely used by all lenders, it’s often misunderstood. In this article, we’ll discuss the debt yield in detail, and we’ll also walk through some relevant examples.

What is The Debt Yield?

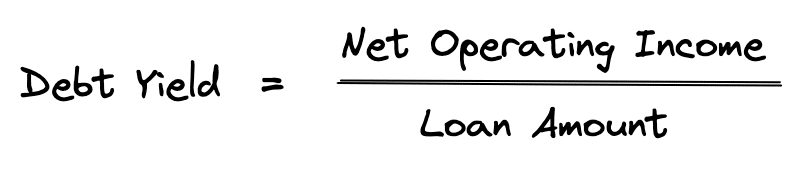

First, what exactly is the debt yield? Debt yield is defined as a property’s net operating income divided by the total loan amount. Here’s the formula for debt yield:

For example, if a property’s net operating income is $100,000 and the total loan amount is $1,000,000, then the debt yield would simply be $100,000 / $1,000,000, or 10%.

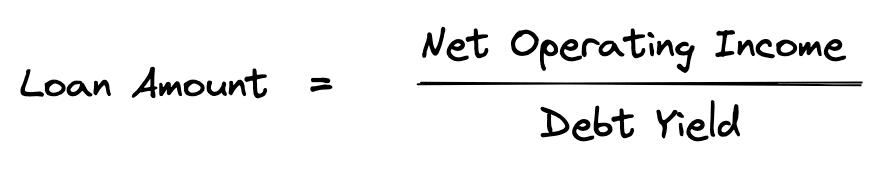

The debt yield equation can also be re-arranged to solve for the Loan Amount:

For example, if a lender’s required debt yield is 10% and a property’s net operating income is $100,000, then the total loan amount using this approach would be $1,000,000.

What The Debt Yield Means

The debt yield provides a measure of risk that is independent of the interest rate, amortization period, and market value. Lower debt yields indicate higher leverage and therefore higher risk. Conversely, higher debt yields indicate lower leverage and therefore lower risk. The debt yield is used to ensure a loan amount isn’t inflated due to low market cap rates, low-interest rates, or high amortization periods. The debt yield is also used as a common metric to compare risk relative to other loans.

What’s a good debt yield? As always, this will depend on the property type, current economic conditions, strength of the tenants, strength of the guarantors, etc. However, according to the Comptroller’s Handbook for Commercial Real Estate, a recommended minimum acceptable debt yield is 10%.

Debt Yield vs Loan to Value Ratio

The debt service coverage ratio and the loan to value ratio are the traditional methods used in commercial real estate loan underwriting. However, the problem with using only these two ratios is that they are subject to manipulation. The debt yield, on the other hand, is a static measure that will not vary based on changing market valuations, interest rates and amortization periods.

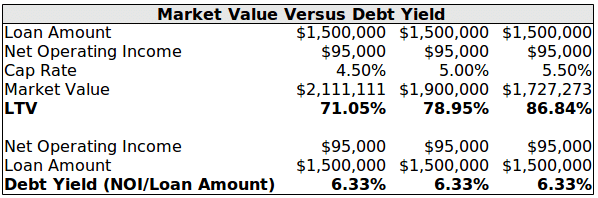

The loan to value ratio is the total loan amount divided by the appraised value of the property. In this formula, the total loan amount is not subject to variation, but the estimated market value is. This became apparent during the 2008 financial crises, when valuations rapidly declined and distressed properties became difficult to value. Since market value is volatile and only an estimate, the loan to value ratio does not always provide an accurate measure of risk for a lender. Consider the following range of market values:

As you can see, the LTV ratio changes as the estimated market value changes (based on direct capitalization). While an appraisal may indicate a single probable market value, the reality is that the probable market value falls within a range and is also volatile over time. The above range indicates a market cap rate between 4.50% and 5.50%, which produces loan to value ratios between 71% and 86%. With such potential variation, it’s hard to get a static measure of risk for this loan. The debt yield can provide us with this static measure, regardless of what the market value is. For the loan above, it’s simply $95,000 / $1,500,000, or 6.33%.

Debt Yield vs Debt Service Coverage Ratio

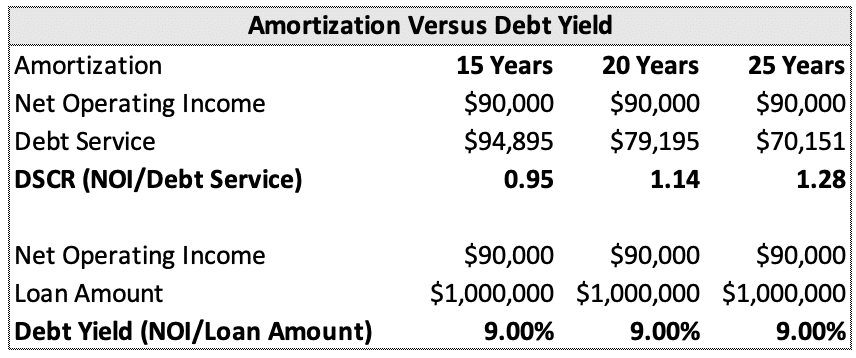

The debt service coverage ratio is the net operating income divided by annual debt service. While it may appear that the total debt service is a static input into this formula, the DSCR can in fact also be manipulated. This can be done by simply lowering the interest rate used in the loan calculation or by changing the amortization period for the proposed loan. For example, if a requested loan amount doesn’t achieve a required 1.25x DSCR at a 20-year amortization, then a 25-year amortization could be used to increase the DSCR. This also increases the risk of the loan, but is not reflected in the DSCR or LTV. Consider the following:

As you can see, the amortization period greatly affects whether the DSCR requirement can be achieved. Suppose that in order for our loan to be approved, it must achieve a 1.25x DSCR or higher. As demonstrated by the chart above, this can be accomplished with a 25-year amortization period, but going down to a 20-year amortization breaks the DSCR requirement.

Assuming we go with the 25-year amortization and approve the loan, is this a good bet? Since the debt yield isn’t impacted by the amortization period, it can provide us with an objective measure of risk for this loan with a single metric. In this case, the debt yield is simply $90,000 / $1,000,000, or 9.00%. If our internal policy required a minimum 10% debt yield, then this loan would not likely be approved, even though we could achieve the required DSCR by changing the amortization period.

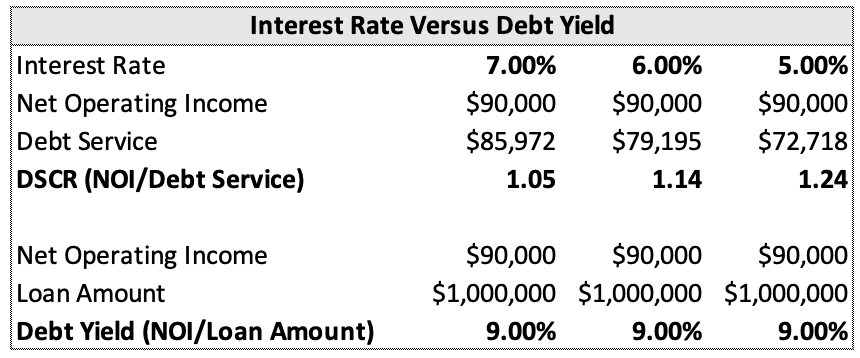

Just like the amortization period, the interest rate can also significantly change the debt service coverage ratio. Consider the following:

As shown above, the DSCR at a 7% interest rate is only 1.05x. Assuming the lender was not willing to negotiate on amortization but was willing to negotiate on the interest rate, then the DSCR requirement could be improved by simply lowering the interest rate. At a 5% interest rate, the DSCR dramatically improves to 1.24x.

This also works in reverse. In a low-interest rate environment, abnormally low rates present future refinance risk if the rates return to a more normalized level at the end of the loan term. For example, suppose a short-term loan was originally approved at 5%, but at the end of a 3-year term rates were now up to 7%. As you can see, this could present significant challenges when it comes to refinancing the debt. The debt yield can provide a static measure of risk that is independent of the interest rate. As shown above, it is still 9% for this loan.

Market valuation, amortization period, and interest rates are in part driven by market conditions. So, what happens when the market inflates values and banks begin competing on loan terms such as interest rate and amortization period? The loan request can still make it through underwriting, but will become much riskier if the market reverses course. The debt yield is a measure that doesn’t rely on any of these variables and therefore can provide a standardized measure of risk.

Introducing CRE Loan Underwriting

The only online course that shows you how lenders underwrite and structure commercial real estate loans

Reviews key loan personnel at each stage of the loan approval process

Learn fundamental credit concepts used by all lenders

Understand the framework lenders use to underwrite any type of loan

5 detailed case studies using actual real world loans

Package of more than a dozen tools and templates you can download and use

60-day money back guarantee

Using Debt Yield To Measure Relative Risk

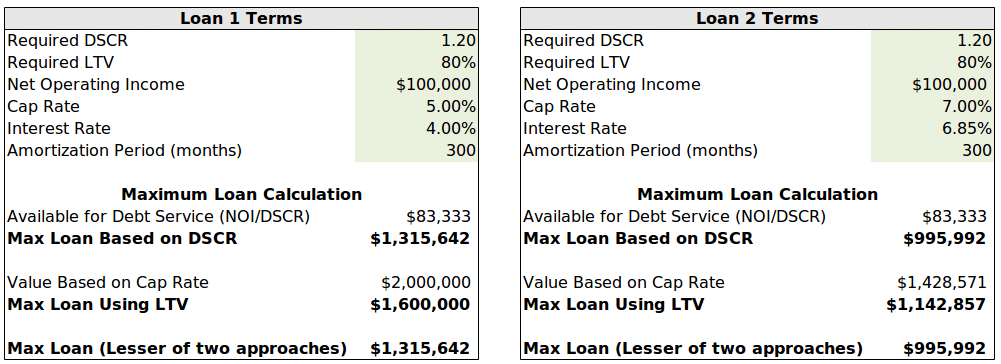

Suppose we have two different loan requests, and both require a 1.20x DSCR and an 80% LTV. How do we know which one is riskier? Consider the following maximum loan analysis for both loans:

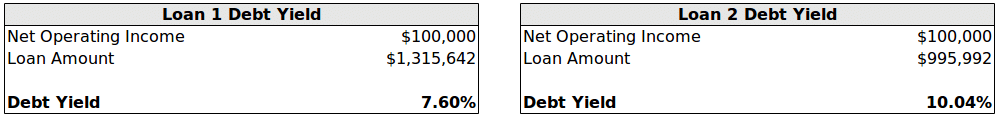

As you can see, both loans have identical structures with a 1.20x DSCR and an 80% LTV ratio, except the first loan has a lower cap rate and a lower interest rate. With all of the above variables, it can be hard to quickly compare the risk between these two loans. However, by using the debt yield, we can quickly get an objective measure of risk by only looking at NOI and the loan amount:

As you can see, the first loan has a lower debt yield and is therefore riskier according to this measure. Intuitively, this makes sense because both loans have the same NOI, except the total loan amount for Loan 1 is $320,000 higher than Loan 2. In other words, for every dollar of loan proceeds, Loan 1 has just 7.6 cents of cash flow versus Loan 2 which has 10.04 cents of cash flow.

This means that there is a larger margin of safety with Loan 2, since it has higher cash flow for the same loan amount. Of course, underwriting and structuring a loan is much deeper than just a single ratio. There are other factors that the debt yield can’t consider such as guarantor strength, supply and demand conditions, property condition, strength of tenants, etc. However, the debt yield is a useful ratio to understand, and it’s being utilized by lenders more frequently since the financial crash in 2008.

Conclusion

The debt service coverage ratio and the loan to value ratio have traditionally been used (and will continue to be used) to underwrite commercial real estate loans. However, the debt yield can provide an additional measure of credit risk that isn’t dependent on the market value, amortization period, or interest rate. These three factors are critical inputs into the DSCR and LTV ratios, but are subject to manipulation and volatility. The debt yield on the other hand uses net operating income and total loan amount, which provides a static measure of credit risk, regardless of the market value, amortization period, or interest rate. In this article, we looked at the debt yield calculation, discussed how it compares to the DSCR and the LTV ratios, and finally looked at an example of how the debt yield can provide a relative measure of risk.